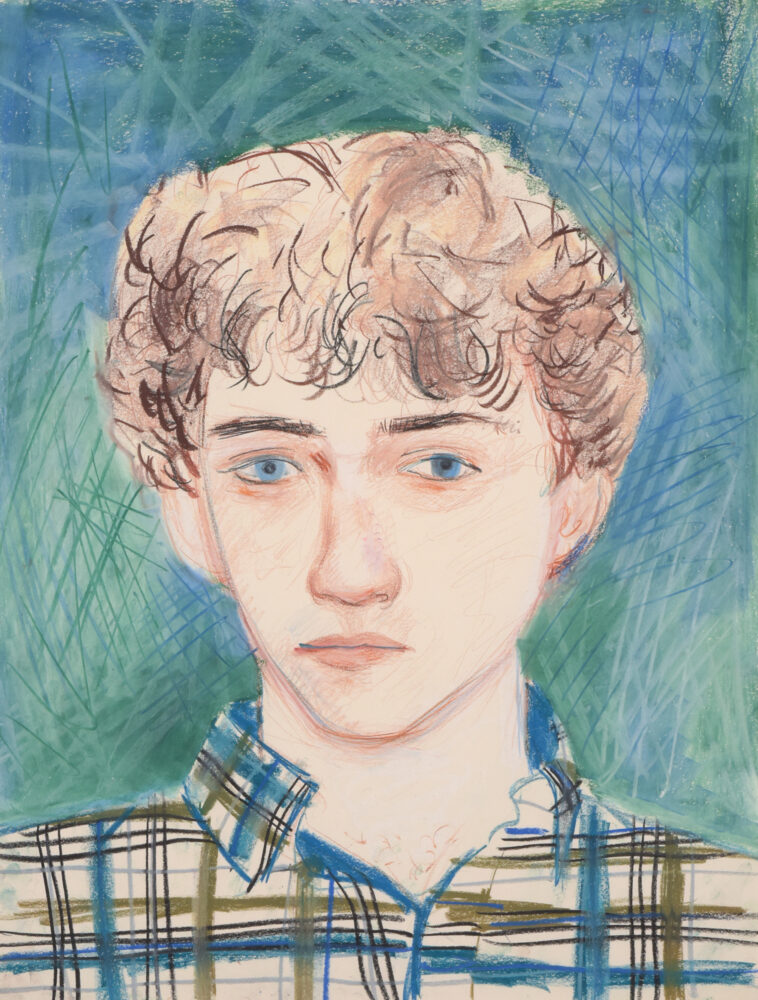

The_Male_Gaze:_From_Larry_Stanton_To_Now

The_Male_Gaze

5th – 30th July 2022